Over the weekend, I had some time to digest a very fruitful and in-depth session with my design team. We focused on learning experiences through play. There is no denying that gameplay has significant educational value. Consider the 2002 Millennium Challenge. The US Dept. of Defense spent over $250 million to explore the scenario of a US invasion of Iran. A retired USMC Lt. Gen, playing for the “red team” (i.e., opposing forces), and shocked US commanders when his opening moves defeated the US Navy during a simulated attack. His tactics were so devastating that the game facilitators had no choice but to reset the scenario, and impose artificial restrictions. His tactics revealed a strategic weakness, and exposed the unknown. Was it worth $250 million? Considering the expensive lessons we learn (or, fail to learn) during actual warfare, I would argue that such simulations are a bargain.

With so much potential (for both learning and fun), we explored game mechanics as a way to make the abstract concepts of digital rights more accessible. We rant into a few obstacles with this approach, but none more frustrating than the fact that there are already several games that attempt to do exactly that. We agreed that we do not need one more in that mix.

Toward the end of that session, I became acutely frustrated by the divide between tactics and strategy. Encryption is important, and I want people to know about it, but I also don’t see it as a solution to systemic issues of user privacy, data collection, and surveillance capitalism. To be clear, I still think that it is a valuable tactic and an essential technology, but it falls short of addressing most of my strategic concerns. Worse yet, addressing these technologies as their discrete parts leaves little room for addressing the issue of digital citizenship, digital rights, and the electronic frontier we all care so much about.

How then, can we present this level of complexity to our intended learners? And *who* are our learners, exactly? We reached consensus that “digital natives” make the most sense — but really it should be everyone who benefits from (or can be harmed by) the internet.

Pictured: a young netizen. There is no way that this kid gave consent for this picture to be distributed, but let’s put a pin in that for now... Intel Free Press — https://www.flickr.com/photos/intelfreepress/8433147083/sizes/o/in/photostream/

Where is the strategy? Where is the awareness? We began to focus these concerns through a framework created by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe, and their “six facets of understanding.” Before we can decide how to address *how* learners will understand this complexity, we first needed to develop concrete goals for learning.

The six facets for learners

Explain: learners can produce written/verbal information relevant to the topic

Interpret: learners can construct a narrative, linking cause and effect for a given phenomenon

Apply: by contextualizing what they know, learners can adapt their model of understanding to solve novel problems

Perspective: learners are able to think through a problem from the perspectives of different actors

Empathize: can think experientially about other’s interactions with a context, and value how they experience it

Self-knowledge: be aware of how that knowledge affects their thinking and decision making. Know the limits of their understanding, and what remains unknown to them

In the game monopoly, children (ages 3 to 10) learn zero-sum capitalism, market failure, scarcity, opportunity cost, property rights, legal penalties, and much, much more. The players get to take on the role of a property tycoon, and quickly learn that there are different layers to the game. This was by design: the original intent of the game was to teach players about income inequality. It is a game born out of the Great Depression. One of the often overlooked aspects of Monopoly is that “house rules” are determined by the players. A game of monopoly need not be cut-throat. The rules can be tweaked to be more equitable for all. This is true beyond the board game context—this is core to the very concept of democracy.

Not knowing how to synthesize something so elegant (to address digital rights), I told the group that what I really wanted was a constitutional convention. I wanted people to take on the 21st century equivalent of Hamilton, Madison, Jefferson, and Washington. I wanted smartphones and powdered wigs, tough negotiations and duels. I wanted people to think about their dissatisfaction of being mere subjects to the kingdoms of Facebook and Google, to having no higher status than “colonist” on a digital frontier.

Could roleplaying be enough? Could personas to represent different stakeholders facilitate a learning experience? How can we get people to take these roles seriously? I had more questions leaving our session than I came in with.

Upon reflection and a white board session with Nandini, we returned to the idea of game mechanics in a learning experience. I think we both retreat to the territory of fun when things get difficult. Indeed, for such a heavy subject, I do want people to have fun, and make the learning happen under a blanket of stealth; people tend to be more open to new ideas when they step outside of their own context to engage in play, and we wanted to leverage that. As I alluded to earlier, this is also true in the context of war games.

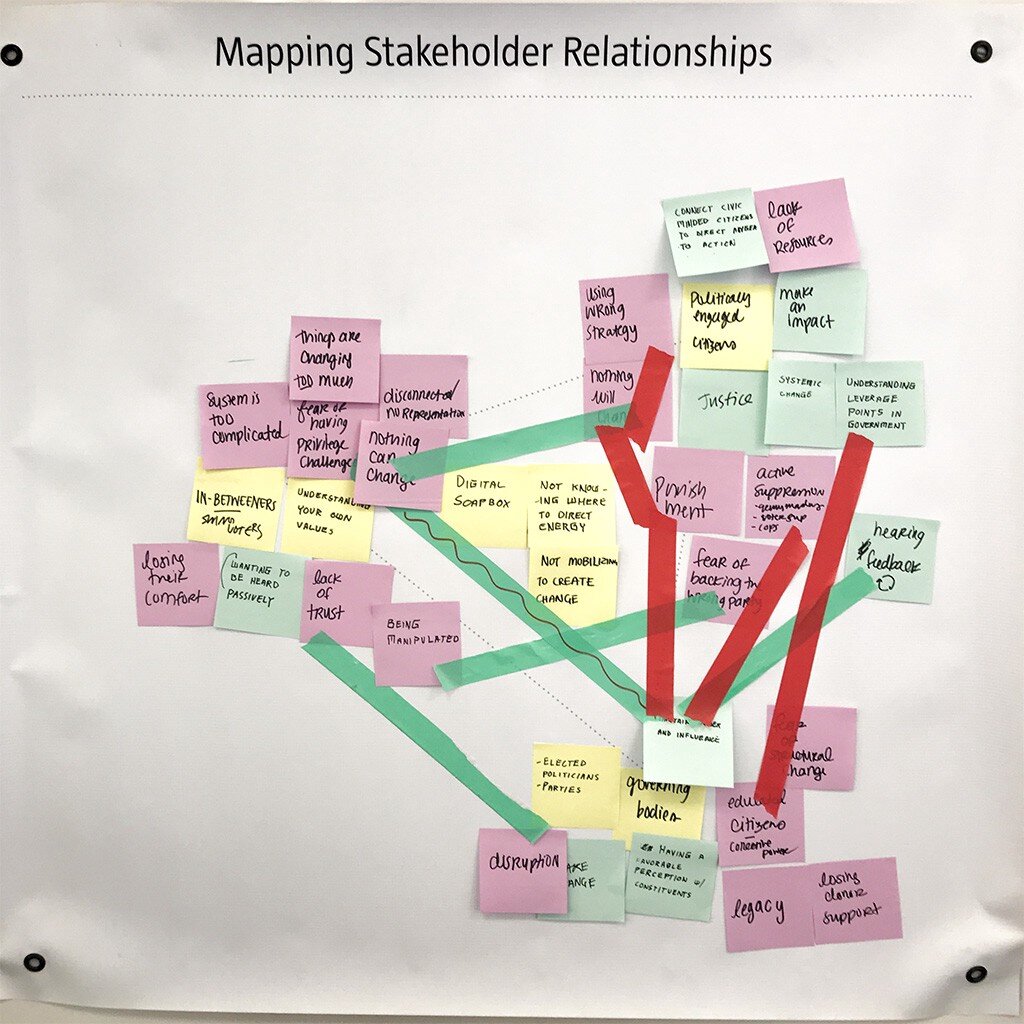

Returning to Wiggins and McTighe, we began synthesizing game mechanics around the six facets.

I’ll do my best to make sense of these scribbles—I promise!

Mechanics under consideration (an incomplete inventory)

Digital and physical mechanics

Hidden agendas

Secret personas

Objectives with dynamic feedback

Inevitable conflict, plausible compromise

We now envision a game, where players use their mobile device as an interface, while interacting in physical space. The players are participating in the first constitutional convention of the internet. They are randomly assigned roles that will dictate their objectives (e.g., a movie and television streaming service, a government surveillance agency, or a social media platform). These personas will act as stakeholders, trying to advance their agenda. Players will take turns, negotiating for an objective to be codified into a digital constitution. Players will then anonymously vote (using their mobile device). As certain provisions are agreed upon, the player’s objectives will change in real-time. For example, an video streaming service is naturally harmed by asymmetrical restrictions on bandwidth… unless they also control that restriction themselves, giving them an unfair competitive advantage over competing platforms. If they “lose” the fight to obtain net-neutrality, their agenda shifts to obtain power over the inequality. Likewise, a government agency and a social media platform might both benefit from anti-privacy measures.

This is as much of a convention as it is a war game.

How does this perform under the six facets?

Explain: players will learn key terms related to cyber security, digital rights, privacy, and the institutional structures governing the World Wide Web

Interpret: to perform well at this game, players will need to engage their critical thinking skills and explore the relationships of a highly dynamic and complex system. They will develop mental models to account for economic, social, and political aspects of 21st century technology

Apply: as their mental model improves, players will begin to think strategically about their objectives, and the objectives of other players. They will improve their ability to persuade and advocate for complex policy positions

Perspective: players will become aware of the competing stakeholders, their agendas, and the consequences of their proposals over time

Empathize: players will learn to value differing and conflicting goals, and will understand the gains and loses for themselves and others

Self-knowledge: players will become aware of the complexity, and will identify gaps in their knowledge through multiple playthroughs